I was nine or ten when I first experienced both the smell of bracken and the nation that is Scotland. It was late July, the start of Glasgow Fair Fortnight, and therefore my parents must have taken me out of my London primary school for two weeks to pack me on a plane to Glasgow, for a fortnight’s camping holiday with my big sister Pat and her boyfriend. It was my first camping trip, too. It took me all the way up the west coast to Cape Wrath and literally changed my life.

My first evening in Scotland was memorable for sitting on a wall eating fish suppers. My first full day began with a curious morning at Pat’s work, where little was done beyond desk-tidying and paper aeroplane competitions. Then, the hooter went, tools were downed, and everybody went on holiday. Northwards first, in the Mini, me surrounded by camping gear in the back seat. We stopped by Loch Garry the first night, off a dead-end tiny road, and camped in a clearing in the bracken by the loch.

Loch Garry was my introduction to midgies. Naively, I thought they were all part of the adventure. I chattered away in excitement behind the mosquito coils, breathing in the strange, new scent from the bracken that for me would ever more be the scent of Scotland. Eventually, Pat interrupted me.

“Margaret, what time do you think it is?”

“Umm, maybe half past eight?” I replied hopefully, knowing my bedtime was at nine during holidays. I wanted to stay up a little longer.

Pat showed me her watch. It was twenty past eleven. Summer in Scotland, long days, even in July. I was persuaded into my all-too-exciting sleeping bag, and eventually fell asleep, though I never saw it get dark. And woke, next morning, to the smell of bracken once again.

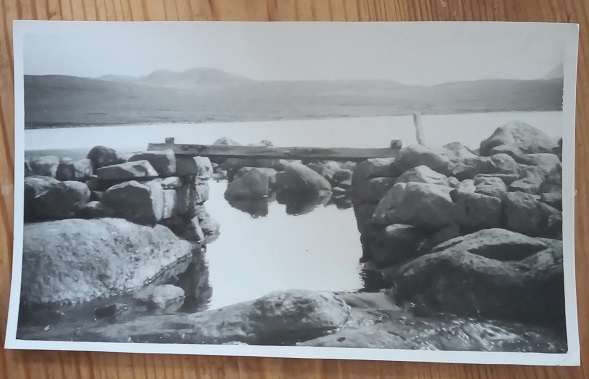

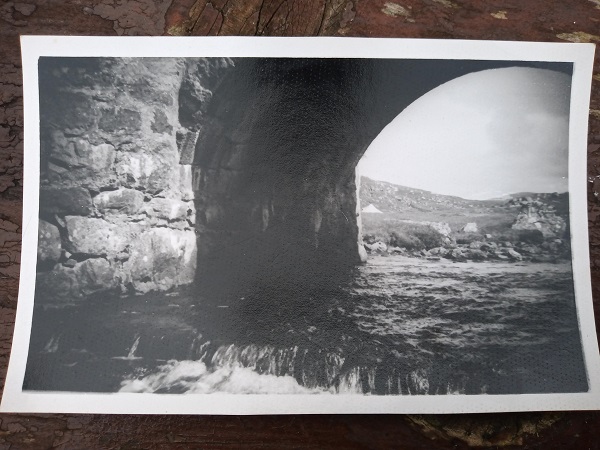

We meandered north and west for nearly two weeks, camping wild up tracks that led from narrow, grass-centred, barely-surfaced roads to the ruins of long depopulated clachans and farmsteads. Sometimes we stayed under bridges, or on beach-paths up which seaweed was once hauled for fields now buried in bracken, their stone walls mere crumbling ridges in the grass. Once, we asked permission from an isolated farm, where the farmer’s wife took the cow for an evening walk each day. We filled our water bottles there, and tried to buy, but were always given, raw milk from the cow.

I trailed after my sister by burns and over cliffs, taking bad photos with my precious box camera, looking for eagles, dizzied by sea-stacks, drinking in a world I couldn’t have imagined from my London suburb. Ullapool, Mellon Udrigle, Achiltibuie, Lochinver, Stoer, Kinlochbervie, Oldshoremore – place names which became indelible in my brain. And the magical mountains of Assynt: Stac Pollaidh the “petrified hedgehog”, Suilven, Canisp, Quinag…. I had not known there was this.

As I inhaled the scents of bracken, I discovered its practical uses. Pitch your tent over it, and it made for a comfortable sleep if your air-bed leaked its air out every night as mine did. Bracken was an indicator plant for dry ground when crossing terrifying bogs (as were heather and, to an extent, rushes. Bog cotton and moss was to be avoided). And being a small child, the bracken generally towered over me, yet I could find paths deep into it’s forest, to child-sized clearings, for private pees or just to hide.

I already knew, from my uniquely progressive and brilliant Scottish primary school teacher, more about Scotland than the average English adult does today. I knew of the Clearances, the Wars of Independence, Burns’ poems and (reluctantly) Scottish Country Dancing. What I learned that fortnight was not facts. It was the country itself, sights, sounds and weather, the star-filled nights and the mists that clung in the whispering air; the colour of the rain; the beauty, the sorrow and the joy. I was never the same again. Although I muttered crossly to myself about long walks with wet feet, and the sheer copiousness of uphill tracks, I was captured. Thereafter, holidays with my parents sitting on crowded beaches in southern England, driving out to bustling “beauty spots” and picnics on the side of the road, were never the same. To their credit, mum and dad realised it, and did their best to incorporate more “adventure” into our trips.

But it wasn’t adventure I craved. I’ve never been very adventurous. It was the scent of bracken.

It was the scent of Scotland.

Thank you.