The ash tree, with its distinctive black, pyramid-like winter buds that sit defiantly opposing each other, was the first native tree I learned to recognise in winter. From the grey, ebony-tipped twigs I stood back to take in the whole glorious form of this tree at maturity: the grace and strength of the downward-sweeping branches, the solidity of trunk and main frame, and the artistic flourish with which the ends of each branch skip briefly skywards following their downward plunge.

Like all deciduous trees, the beauty of its structure is revealed annually at leaf-fall. We may love and appreciate our trees in summer, but in winter, we can truly see them. I never tire of looking at trees in winter.

Sadly, the monumental frozen-motion glory of the mature ash is a sight less and less available to us. Ash die-back disease is caused by a fungus (Hymenoscyphus fraxinea) which attacks and infests the bark, leading to wilting of leaves and die-back of those optimistic, sky-seeking terminal twigs. Jaggy, stunted branch-ends and lesioned bark are more often what we see today. The spores are wind-blown, and so it has spread inexorably through Europe. There seems to be little point in felling affected trees, since the fungus spends part of its life cycle proliferating in leaf litter. In pockets where old ash trees are isolated from larger populations, such as Glen Tilt in Highland Perthshire, the majesty of the winter ash can still be seen.

There will be resistant trees, and much is being done to find these, identify their genetic codes, and breed from them. We can only hope the ash tree’s absence from the landscape is temporary.

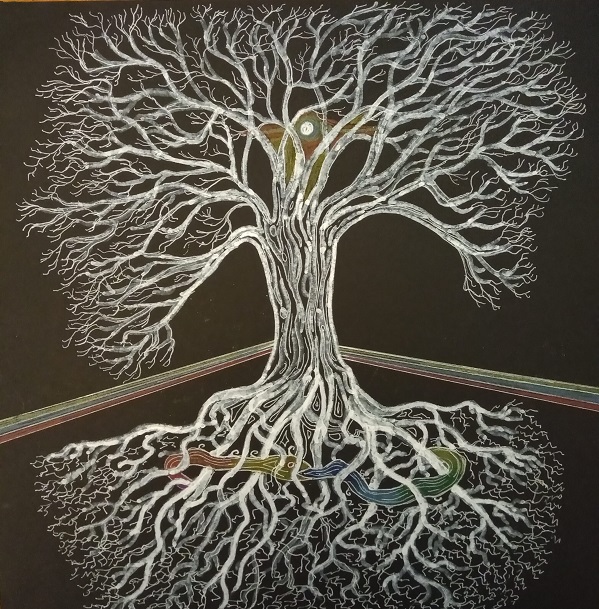

But the Ash Tree has an existence outside the biological. It is – and long has been – a symbol, a magical entity, a talisman. In Norse and Germanic mythologies it is Yggdrasil, the World Ash Tree. Its branches reach into and hold up the heavens; its roots delve deep into the dark caverns of the underworlds, where the serpent-dragon Nidhogg gnaws at its roots. Between the two lies everything we know, and much that we don’t. Three women, the Norns, sit below its mighty branches, tending the World Tree and spinning, spinning, spinning the fates of gods and humans.

The Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge are other expressions of Yggdrasil. Odin, father and chief of the Nordic pantheon, presents as a seriously flawed, doubtful and often misguided god. (To be fair, they all do.) Maybe that’s why he disguised himself as the Wanderer, with his wide-brimmed hat (echoed in the character of Gandalf in Lord of the Rings?) and ash staff cut from Yggdrasil, roaming the Earth in search of knowledge and enlightenment. Ultimately, the tale goes, Odin had to hang himself from the Tree, wounded by the ash spear, for nine days and nights, to find the wisdom to save humankind.

Should the Norns cease to care for Yggdrasil, or malevolent forces overtake it, like our blighted ash trees, it will die, and the rooster Gullinkambi will crow from its withering canopy, proclaiming Ragnarok – the Twilight of the Gods.

Will we save our earthly ash trees? Who are the gods whose twilight we would seek in return?

May 2021 bring a sea-change in our relationship with nature, may we all be safe, may Yggdrasil bear new shoots of hope, and may the ash tree survive.