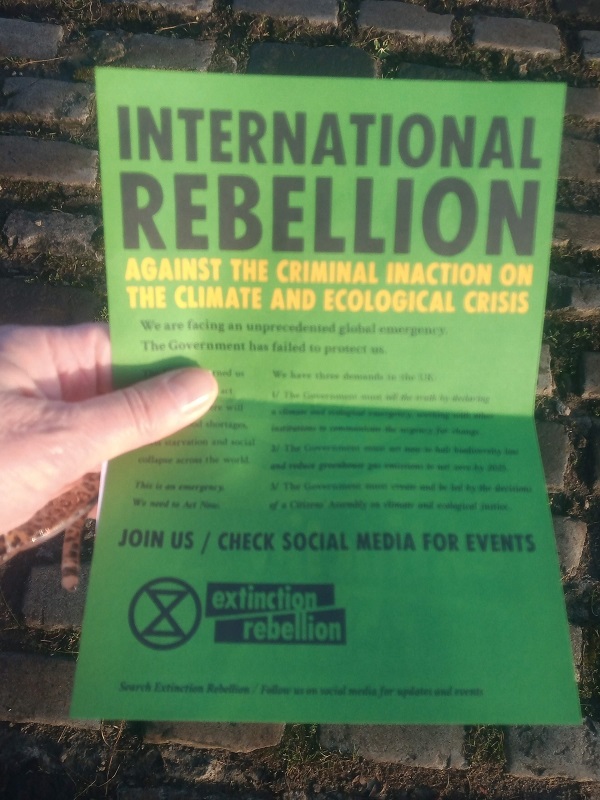

How often in the past year have you heard someone say, “You never know what’s around the corner”? Or felt anxiety because you really, really don’t know what is happening or going to happen to you, and the future is obscure? We got caught in the Christmas Covid Car Crash, and are just mentally reeling from a close encounter with coronavirus. We emerge, cautiously and with reluctance from tests and self isolation, while our close family recover from the virus. We emerge into another lockdown, and feel relieved. Self-isolation, let me tell you, can be addictive when you’ve been scared, and realised how ill-prepared you are for dying.

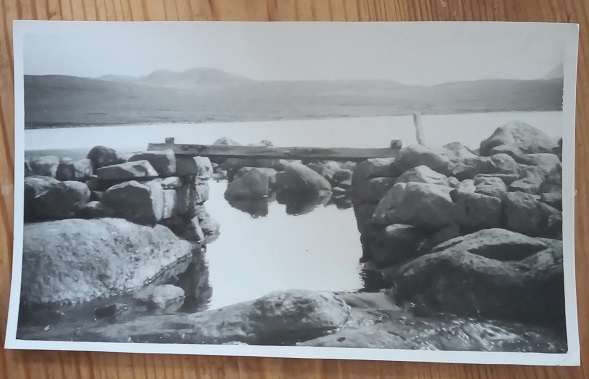

Back in late summer, when such things were still possible, we had a two day camping trip to Glen Esk. On the second day, we decided to take a short and easy walk up Glen Lee. Short, to give us plenty of time to enjoy a cycle down Glen Esk as well. At first, we decided, we’d just go to the start of Loch Lee and turn around. But just beyond the point where the Water of Lee calmly enters the loch, we could see the ruins of a church or chapel by the waterside. “We’ll just go to that and explore.”

The tiny old parish church of Glenesk had not been used in a good while, but the ancient gravestones, carved with faces and bones and what look like crossed spades, suggested a long history. In fact, a church of some kind is believed to have stood here since at least the 8th century. The sun on the well-tended grass invited a long dawdle and a picnic, and then we ambled along the track by the loch. The other end of the loch wasn’t quite visible, so we thought we’d “just go round the next corner” to see it.

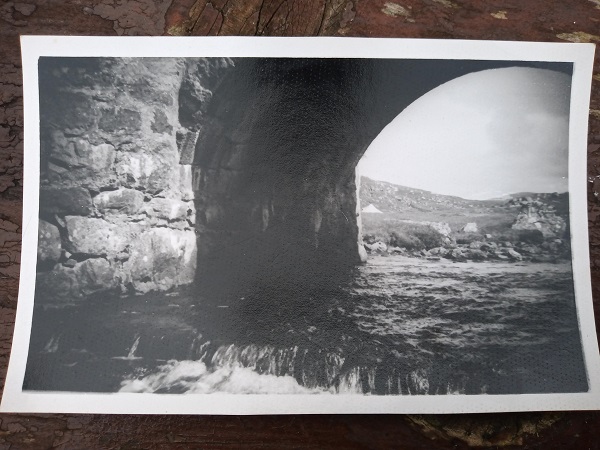

And so we began the inevitable daunder-of-curiosity which besets all walkers in new territory – the drive to see what’s round the corner, or over the next hill. Round and past the far end of the loch, skirting the flat plain where we looked for the signs of ancient habitation, past deserted farmsteads and into the steep-sided valley, up into the purple heather. Every crag we rounded gave us sight of another; we had to know what came next.

Eventually, we saw the Falls of Unich, where tracks to right and left might have given us a circular walk. But we didn’t have a good enough map, and still wanted a cycle. So we returned the way we came, marvelling lazily at the carnivorous sundews and butterworts in the ditch by the track, stopping to watch a hen harrier swooping low over the crags and rising again, while we, in turn, were closely observed by ravens, shouting harshly at our passing. Before we got the bikes out, we had time to admire the forbidding Invermark Castle and the tempting Hill of Rowan, surmounted by the imposing Fox Maule-Ramsay monument.

On this short walk, we left many corners not turned. Maybe we’ll go back. Maybe we won’t. Truth is, none of us knows, or ever has known, what’s around the corner, even when we succeed in deluding ourselves that we can plan ahead and things will always turn out as we planned. The future’s the un-turned corner, and we can only know for sure about the corner we’re standing at.