(It’s taken me a while to write this walk. I did it the day the clocks went forward, end of March, and today they went back again. My 14 year old collie died in early summer, and this was the first walk I decided it would be unfair to take him on, so it was a bit poignant; and weird not to have him beside me all the way.)

It began at the CLEAR Community Garden in Methil where I left Andrew to deliver a workshop. CLEAR stands for Community-Led Environmental Action for Regeneration, and is a very active charity whose stamp is all over the former mining towns of Methil and Buckhaven in Fife. We’ve worked with them a lot over the years – their compulsion to fill every available space whether roadside or cliff-top with fruit trees was one of the inspirations that got us into orchards in the first place. The Methil garden was pretty stunning; I had a good look round to admire the recycled materials, the superb compost bays (I do love a good compost heap) and pear trees about to blossom, before heading off into the cold, breezy sunshine.

Zig-zagging through Methil, side-stepping CLEAR plantings on the edges of parks and in vacant plots, till the town had morphed into Buckhaven, or Buckhyne if you like, the place of superlative pies and hidden histories, from the extravagant exposure of Fife coast geology, the sturdy cottages of Cowley Street and relics of the long-disused mine railway – all explained in panels erected by CLEAR and Fife Council.

I’ve become rather fond of urban walking lately, for the unexpected quirks of history, and opportunities to see the extraordinary hiding behind the mundane. Here, I learned of the “lost village” of Buckhaven Links, which grew, mushroom-like, on the shore when the Church of Scotland had one of its fallings-out and mislaid a large part of its congregation. Buckhaven Links did not survive too long, and is now buried under the Buckhaven Energy Park, a darkly towering set of anonymous edifices over the wall from the street.

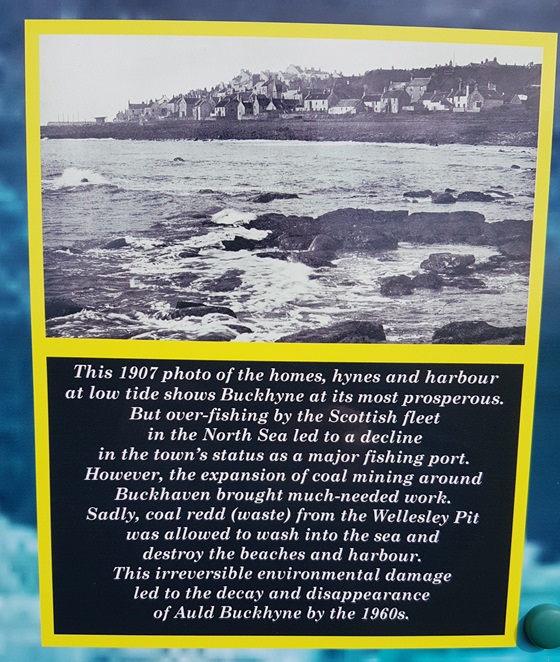

That road took me past rows of houses with signature Fife/East coast crow-stepped gables to where Buckhyne Harbour once was, until it was abandoned due to over-fishing and used as a repository for mining spoil. Beyond the harbour site, a scramble through rocks and there was the beach, for a while and pre-pollution a popular holiday and day trip destination for Fifers and those beyond the kingdom.

Up, then, climbing skyward the Buckhaven Braes, lit by the silver of blackthorn blossom and the gold of Sea Buckthorn, peppered with orchard trees, all labelled, all immaculately pruned and protected, the coast path lined with daffodils in flower, until this extraordinary little town was behind me and I marched along westwards towards East Wemyss.

It was the East Wemyss caves that had been bothering me ever since reading that Val McDermid novel; not just to imagine fictional murders, but to see where Picts had carved strange images in bygone centuries, where people had dwelt, sheltered, hidden, picnicked and stored precious things. But first, when I passed through the woods, I came upon Macduff’s Castle – an impressive ruin whose stonework exhibited all the artistry of a carving, it is so tastefully eroded. All around its roofless vaults grew great clumps of Alexanders, a shiny-leafed, celery-like edible plant not native to these parts, but where it takes off, it does so with enthusiasm. I circumnavigated the castle before heading down the cliff to the caves.

I had been warned that the best bits of the caves were gated off by substantial railings, in order to protect the ancient carvings. You can get a guided tour of them if you go to the museum in East Wemyss, but I didn’t want that today. So I stood outside Jonathan’s Cave and used my imagination instead, then stood inside the Doo Cave, where dozens of little cubicle nest holes have been carved out of the soft red sandstone to accommodate the doos, kept for meat and eggs in years gone by. At the large Court Cave, I did my exploring along with other visitors until my excitement subsided.

Then I walked on, the sunshine now spring-warm, past a gaggle of East Wemyss monuments and memorials, side-stepping mine ventilation shafts, to re-join the path by the sea. Rafts of eider ducks sailed by, making their weird, cooing, gossipy calls, and cormorants lined up on rocks. Strange but recent sculptures in stone arose against the skyline like sentinels; I added to them, noticing how the stiff uprightness of last year’s teasel seedheads mirrored their form. Under the precipice on which the relatively modern Wemyss Castle teeters, and I was into happy little West Wemyss, basking, and its lovely cafe for tea and a well-earned salad.

Looking forward to the next Fife coast exploration!

Pockets of peaty marshland, studded in autumn by vivid blue sheeps’ scabious and emphatically solitary flowers of the Grass of Parnassus, spiral around flat pools of oily water, reflecting snatches of sky. Larger raised bogs, pillaged in previous centuries for their peat, lie flat and sullen. When the peat was no longer wanted, they grew conifers on the “useless” land.

Pockets of peaty marshland, studded in autumn by vivid blue sheeps’ scabious and emphatically solitary flowers of the Grass of Parnassus, spiral around flat pools of oily water, reflecting snatches of sky. Larger raised bogs, pillaged in previous centuries for their peat, lie flat and sullen. When the peat was no longer wanted, they grew conifers on the “useless” land.  Now the conifers are retreating after the long-forgotten glaciers; the water returns; dragonflies, amphibians and sphagnum once more fill the horizontal expanse between the forest. Heaths and ling guide the trespasser to the dryer paths, and felled branches bridge the bog where water maintains its horizontal sovereignty.

Now the conifers are retreating after the long-forgotten glaciers; the water returns; dragonflies, amphibians and sphagnum once more fill the horizontal expanse between the forest. Heaths and ling guide the trespasser to the dryer paths, and felled branches bridge the bog where water maintains its horizontal sovereignty. In fields by the loch, the damp rises in horizontal layers, coating logs and stumps and gate-posts with moist, green mosses and algae. In one field a whole tree fell, years ago. In this damp environment it has not died, but adapted to its horizontal status and continued to grow; a miniature forest of shoots, epiphytes and primitive plants along its horizontal trunk.

In fields by the loch, the damp rises in horizontal layers, coating logs and stumps and gate-posts with moist, green mosses and algae. In one field a whole tree fell, years ago. In this damp environment it has not died, but adapted to its horizontal status and continued to grow; a miniature forest of shoots, epiphytes and primitive plants along its horizontal trunk.