A Post for West Stormont Woodland Group

https://www.weststormontwoodlandgroup.org.uk/

Five Mile Wood today is a wood part-forest, part scrub and heath. When the Forestry Commission took out the last tree crop, they left a fragile fringe, largely of Scots Pine, around the north-east side of the circular path that now forms almost the only access to the bulk of the wood. The Benchil burn trickles through and under the path here, on its way to the Tay, and water from the high water table of the central area percolates into a series of pathside ditches and curious water-holes made by a forestry digger. This is the wet side of the wood. While the trees must take up a lot of water, their canopy also prevents evaporation, and after recent heavy rain, the glades and ditches are alive with summer flowers and butterflies.

Heath Bedstraw and Tormentil are strewn along the path edges like yellow and white confetti, and red clover flourishes heroically on the banks. Meadow Vetchling and Bird’s Foot Trefoil are visited by brown ringlet, wood white, common blue, and pearl-bordered fritillary butterflies, who pause and spread themselves out infrequently on warm stones and bark shreds on the path.

Bright Hawkweeds grow tall and enthusiastic, stretching for the dappled sun that today is scorching whenever the clouds part. In the cooler shade, sweet-scented Valerian grows. It prefers a damp habitat, and its white to pinkish flowers are nectar-rich, a magnet for more butterflies. This plant is widely used in herbal medicine, its roots being a soporific. Common Orchids and Viper’s Bugloss unusually share a habitat. Here and there are thistles, always a good bee-flower, and today a relevant newcomer to central Scotland, the Tree Bumble Bee (Bombus hypnorum) is engrossed with nectar collection.

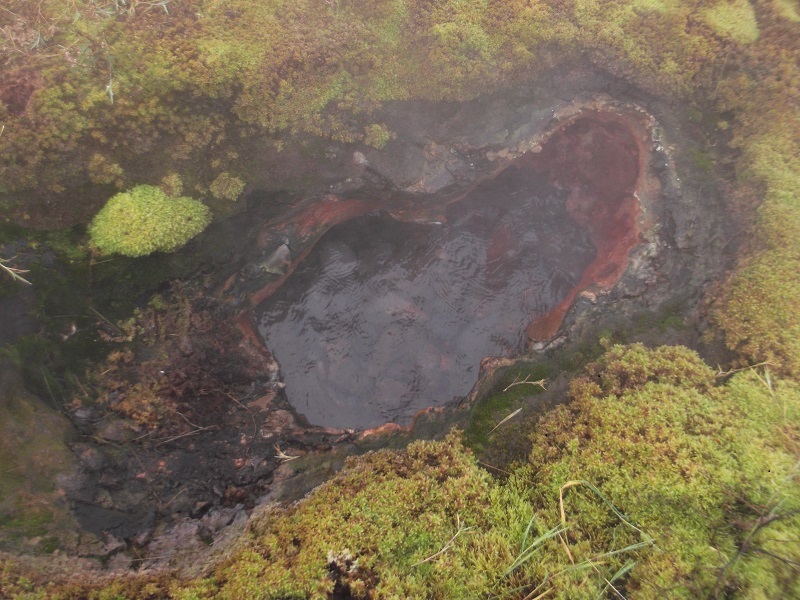

The true nature of this tract of land gives itself away in the damp bases of ditches and where vague deer tracks can be followed a short way into the springy sphagnum. It is part of a network of raised bog, myre or moss that probably once were joined. King’s Myre in Taymount Wood is another remnant. Damselflies hover over the multicoloured water forget-me-nots in conjoined pairs. The Lesser Spearwort dazzles from many a watery ditch and aptly-named Ragged Robin, dances its frilly pink skirts by the burn. Acid-loving and ubiquitous tormentil abounds, and bell heather is in flower already – another treat for insects.

We humans are such visual creatures, and it’s the flowers that draw us and grab our attention. But flowers are the tip of the ecological iceberg of the wet side of the wood. Ferns, grasses, unidentified rushes and reeds are the matrix of this habitat, while unnoticed and unobtrusive, the sphagnum mosses proiliferate, and go on with their work of creating peat, holding onto water – and capturing carbon.

How the woods work to heal us.

Clockwise from top left: Red Clover, Valerian, Viper’s Bugloss, Ragged Robin, Common Spotted Orchid

Everyone should leave their comfort zone behind from time to time, though, and if you venture into The Moss there are rewards. It’s called “moss”, because in most cases that’s what makes it – sphagnum mosses of breathtaking colour and beauty, slowly expanding and dying away to leave peat. Mosses are primitive plants dependent on water for reproduction, and you can be sure the brightest patches will be the wettest. Sphagnum holds an incredible quantity of water. Its uses range from wound dressings (it is naturally antiseptic) and hanging baskets to impromptu disposable nappies when walking with babies! Rushes, too, are useful – think matting, cattle bedding and rushlights – and if you can balance on the clumps as stepping stones, they will see you across a wet patch of moor.

Everyone should leave their comfort zone behind from time to time, though, and if you venture into The Moss there are rewards. It’s called “moss”, because in most cases that’s what makes it – sphagnum mosses of breathtaking colour and beauty, slowly expanding and dying away to leave peat. Mosses are primitive plants dependent on water for reproduction, and you can be sure the brightest patches will be the wettest. Sphagnum holds an incredible quantity of water. Its uses range from wound dressings (it is naturally antiseptic) and hanging baskets to impromptu disposable nappies when walking with babies! Rushes, too, are useful – think matting, cattle bedding and rushlights – and if you can balance on the clumps as stepping stones, they will see you across a wet patch of moor. Finally, there is the alluring bog cotton-grass – a guarantee of treacherous wetland just waiting to suck you down – but such an unusual flower and how beautiful waving massed in a moorland wind – white woolly standards raised to announce a weird, wonderful and ominously wet world of plants!

Finally, there is the alluring bog cotton-grass – a guarantee of treacherous wetland just waiting to suck you down – but such an unusual flower and how beautiful waving massed in a moorland wind – white woolly standards raised to announce a weird, wonderful and ominously wet world of plants!