Comfrey is in the Borage family of plants. There are various species, strains, and cultivars, which all have similar properties. The one which spreads unrelentingly in my garden is the Tuberous Comfrey (Symphytum tuberosum), which is low growing, spreading (via its knobbly, tuberous roots), and has dingy off-white to cream flowers. I am in negotiations currently with Tuberous Comfrey to spread unrelentingly where it can out-compete the ground elder, rather than among the potatoes. This species, along with Common Comfrey (S. officinale) is a native of Britain. A number of imports and acquisitions by Henry Doubleday in the 1870s led to an important cross between Common Comfrey and a Russian species, S. asperum. The hybrid became known here as Russian Comfrey (S. x uplandicum).

Common Comfrey has other common names: Knitbone and Boneset. The generic name Symphytum means “to join together”. The specific name “officinale” indicates medicinal value. (Readers of my last post may see where I’m going here!). Comfrey roots and leaves have been used for many, many centuries in poultices (mainly) to treat sprains, bruises, inflammation, cuts and sores. Comfrey contains allantoin, a chemical which is crucial to cell regeneration and healing. In my garden, the unruly Tuberous Comfrey disappears during winter, but I also have two Russian Comfreys which don’t. One of them used to be variegated, but soon reverted to green and vigorous.

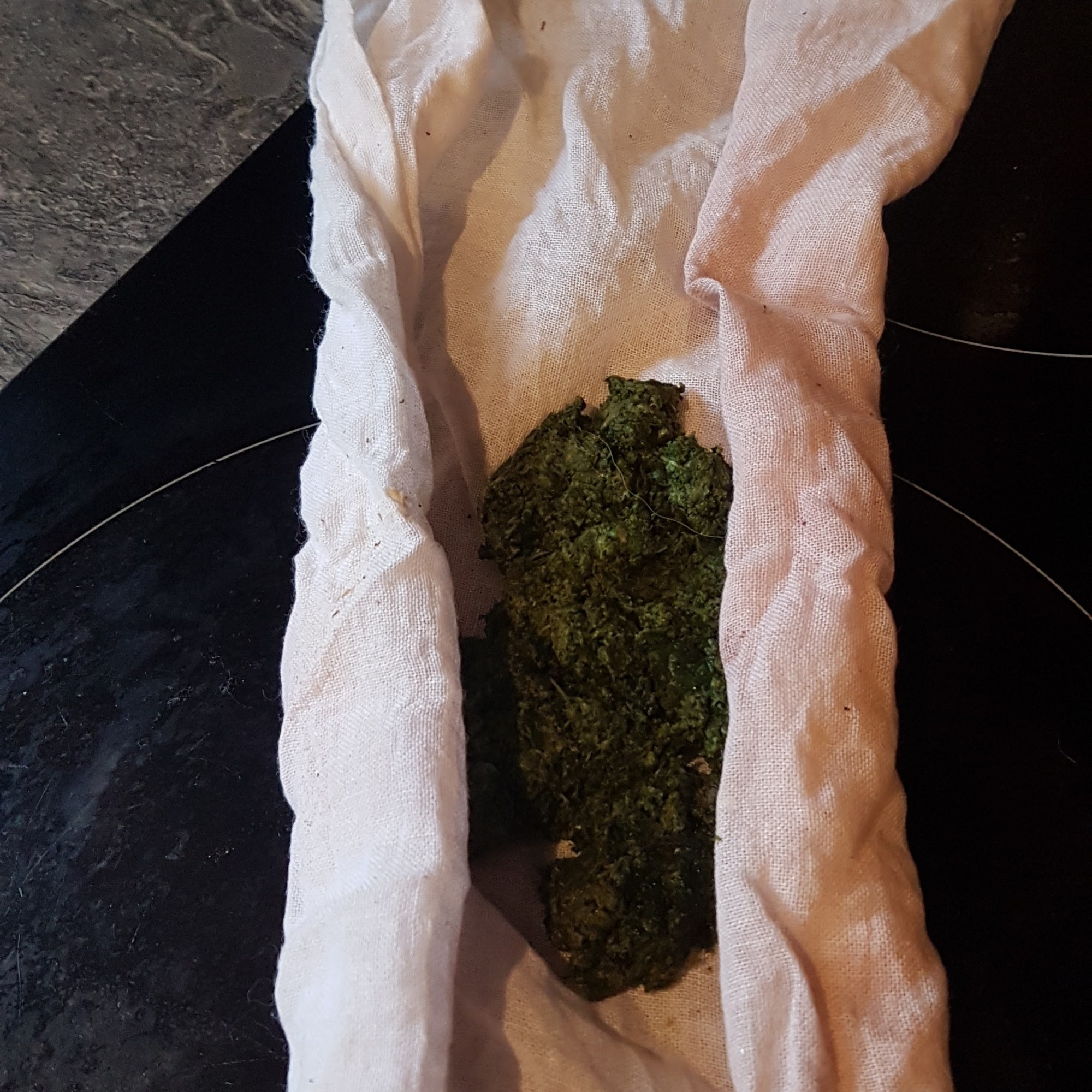

Therefore, in the mild weather between Hogmanay and the end of last week, I manoeuvred myself laboriously up the garden on my crutches, to pick the freshest leaves (yes, there were some!) from the plants. Roots may have been better, but digging isn’t in my current skill-set. A knee with anonymous sprains and tissue damage and a minor fracture of the tibia was going to get the comfrey treatment. I made the poultice very easily, by zapping the fresh leaves to a dark green liquid and mixing it with flour. A square of muslin, folded at the edges to stop the poultice oozing down to my ankles, held the comfrey against the affected bits of knee. An elastic tubular bandage kept it in place, over which went trousers and the leg brace. I did this for 4 days consecutively, but removed it from sight when I went for the fracture clinic appointment. (Self-treat? Who, me??)

On the X-rays, it was very hard to see where the fracture is now, but the doctor pronounced everything was well placed to heal completely, given time. Leg brace for at least another month! Then the weather turned snowy, followed by the customary January freeze, so the Comfrey pharmacy is temporarily closed. I’ll never know for sure how far it is contributing to healing, but that’s no problem, I am happy to be my own experiment in this.

Now to the other uses of Comfrey, including compost. The extravagant growth of the various comfreys which Henry Doubleday imported and which interbred led the organic movement pioneer Lawrence D. Hills to found a field station in Bocking, Essex, dedicated initially to research and breeding of comfrey strains for agricultural and horticultural use, named the Henry Doubleday Research Association. The best-known strain is probably “Bocking 14”. Later, HDRA became the influential Garden Organic charity, with thousands of members. I met Lawrence Hills a couple of times, when I switched from teaching to horticulture and was looking for a year’s work placement as prerequisite to starting a course at Writtle Agricultual College. He was so charming, so enthusiastic, so hard-working – and I was so looking forward to working and learning in an organic garden and taking part in field research. But organic was still considered the domain of hippies and weirdos as far as Writtle was concerned. I was told that HDRA was NOT ACCEPTABLE as a PROPER horticultural placement, and I ended up on a bedding plant nursery. Learned a lot, but you know how I just adore bedding schemes……!

But I grow Comfrey. I would never be without it in the garden. The lovely purple, red and white flowers attract every kind of bee in the district, it suppresses weeds, and is so vigorous I cut both the Russian and Tuberous back several times during the year. Most of the green material goes into the Comfrey bin (joined by excess nettle tops). The bin has a lid but no bottom, and it stands on a perforated metal square (actually a redundant queen excluder from beekeeping), which is balanced on an old washing-up bowl. Into the bowl collects a dark, viscous, evil-smelling liquid – Comfrey tea! NOT for drinking, but for use, diluted, as a liquid feed for tomatoes, vegetables and any plant looking under par, just as Lawrence Hills told me all those years ago. Many gardeners believe Comfrey tea confers disease resistance to plants as well as a nitrogen boost. I don’t add any water to the bin, and the dry material left goes onto the adjacent compost heap. Sometimes I add fresh Comfrey to the heap if it’s being a bit tardy in decomposing – it acts as an activator. Another great thing to do is liberally cover the ground between developing plants such as courgettes with fresh Comfrey leaves as a mulch. Not only will they decompose happily in situ and directly feed the plants, they help to warm the soil and stop weed seeds germinating. (TIP: Don’t accidentally mulch with tubers still attached!)

I also eat Comfrey leaves. Now, my herbalist friends will tut-tut, because Comfrey also contains alkaloids which can damage the liver, to a point where cancerous tumours may develop. I can understand reluctance to prescribe it for internal use. Most of the alkaloids accumulate in the roots and the older leaves, and laboratory trials on unfortunate rats indicate that you’d really need to eat or be injected with an impossible amount of Comfrey to have such a reaction. Nevertheless, I stick to young leaves, in moderation, as a delicious vegetable in combination with nettles and other spring greens. They fill the so-called hungry gap abundantly well, and are a tasty substitute in any recipe involving spinach. Covered in beer batter and deep fried, individual leaves are a really, really bad-for-you treat!

But whether you eat it or not, Comfrey is for life – in more ways than one.

Poultice, now there is a word to conger with, taking me right back to the days of those hot Kalin poultices that were liberally placed on me as a boy. you say that you will never know whether Comfrey contributed to your healing – since you clearly believed in the healing power of Comfrey it did, as in placebo.

LikeLike

Hi Margaret

A very Interesting post. My wife and I have a large comfrey patch in the back of our garden, but i haven’t really done anything with it. To be honest it’s a bit of a nuisance

The comfrey plants grow so rapidly, it’s a bit of a nuisance. The comfrey patch is always trying to colonise more and more garden. So I periodically I remove some of the plant matter and just use it as compost. I would certainly be very wary about consuming any comfrey due to the alkaloids

The following article is interesting BUT I suspect that you’re probably aware of this already!!

https://www.healthline.com/health/what-is-comfrey

Steve

LikeLike

On a separate note. Glad you’re on the way to recovery!!

LikeLike

Thank you! And for the healthline article…I’ve looked at quite a lot of the research on it…. I guess its a matter of weighing the “links” with alkaloid damage against its history of use and making personal choices – mine is to consume the young leaves only in moderation. I keep thinking, alcohol destroys livers for sure but no-one seriously suggests banning it……

Do you know which comfrey you have? I find the Russian fairly biddable, but the tuberous is outrageous !

LikeLike

To be honest I’m not sure. We were given the plants by a neighbour who just told us it was “comfrey” without specifying which particular species it was. The PlantNet app on my phone told me the most likely possibility was Symphytum grandiflorum (Creeping comfrey) but was only 35% certain.

I should have taken some photos when it was flowering to help it a little!! If you want to have a look and give me your opinion drop me an email to info@explainingscience.org and send you a picture

LikeLike