A Story for Christmas, that may be Familiar

In the year 938AD, it was, as usual, a harsh winter in the Dukedom of Bohemia. Roads into and out of Prague were treacherous with ice, and snow lay deep on the sides of Petrin Hill. Vaclav, Duke of Bohemia, gazed gloomily from the window of the castle, down to Vltava, flowing icily through the town. It was a feast day, St. Stephen’s, and Vaclav could already detect the mouth-watering smells of roasting pork and steaming vegetables rising up from the kitchens.

“Wine,” he muttered, “something red, rich and warming”. He called for his page.

“Here, lord,” came a sleepy-sounding voice from a back room, and a very young man appeared, rubbing his eyes.

“Asleep again Pavel? Cold getting to you too, is it? Run and fetch us a flagon of red, and I might let you have a sip.”

Pavel slipped off, and Vaclav turned his eyes across to Petrin, where he doubted the monks would be very happy in their prayers today. Toasting their toes in the warming house, if they’ve any sense, he thought. Thus, he was surprised – and not a little indignant – to glimpse a small, dark figure, bent against the drifting snow, skirting the edge of the woods that bounded monastic lands.

“Pavel,” he said to the returning page, “Look out there. Is that man insane?”

Pavel gravely followed his masters gaze, then gasped in an astonishment that seemed to Vaclav not a little exaggerated. “My Lord!” he cried in righteous indignation, “a trespasser! What a nerve! How dare he? I’ll get onto it right away, I’ll tell the guards to go and arrest…..”

“No, no, boy, don’t get your tunic in a twist! What’s it to me if he tramples a bit of grass? But do you think he’s in his right mind, going out in this weather?”

“Why, sir?”

“Well, would you be out there today?”

“Certainly not, your lordship, give me a warm fire any day to snooze by. I expect that’s what old Peter is aiming for too.”

“Old Peter? You know him?”

“I know of him, sir. He sometimes helps in the fields in summer.”

“Does he now? So why is he not tucked up by his fire today?”

“He’ll not have one, unless he manages to find a bit of firewood. Old Peter never has wood, he can’t afford it.”

Vaclav peered out again. “Why yes, he seems to have a wood-carrier on his shoulders. But not much in it – the guards will have taken all the wood there.”

“Yes, sir. For the castle,” Pavel put in quietly. Vaclav looked suspiciously at him, but the page’s face was blank.

“Where’s this man’s house then, Pavel?”

“House? He doesn’t exactly have a house, sir…”

“Doesn’t have a house?? What does he have, for heaven’s sake?”

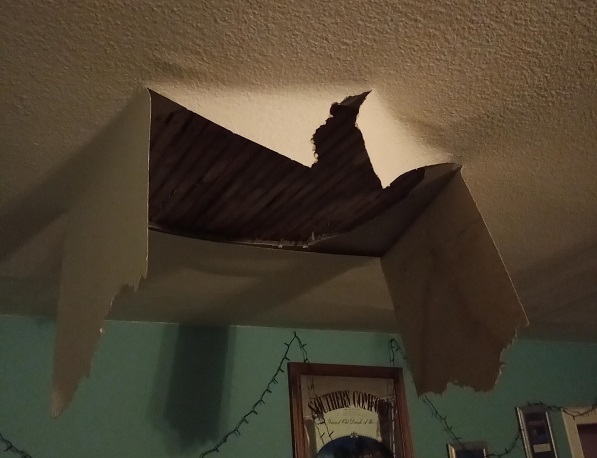

Pavel considered. “Well, there’s a sort of cave, an overhang, near the falls of St Agnes, at the back of Petrin. Peter built a sort of cabin onto the front, and….”

“Do you mean to tell me, boy, that even in midwinter, this man not only has no fire, but scarcely a shelter? What about food? Don’t tell me the man doesn’t eat!”

“Not much, your Lordship. Old Peter doesn’t have much of anything.” They gazed silently out to where the old man struggled against the snow, stumbling in drifts, a pitiful bag of wet, thin branches on his shoulders.

Vaclav silently paced the room, a look of worried amazement on his face. Finally, he turned and seized the page by the shoulders.

“Well today he’ll have something,” he said quietly, “today this man will enjoy St. Stephen’s feast with us. First, fetch that joint of pork I can smell – and some sausages and dumplings.”

Pavel’s face fell, for he usually enjoyed the leftovers from a roast joint himself. But he dared not argue with the determined-looking duke, and went for the food, to the rage and astonishment of the cook.

“Good!” exclaimed Vaclav. “Now, vegetables – a sack of turnips and carrots, and enough jars of pickled cabbage to last a week. Oh- yes – better get a sled ready”. While Pavel busied himself with this task, Vaclav tied up two large bundles of the dry, split logs that were waiting by his fireside.

“There now,” he muttered, that’s all I think.”

“Excuse me sir,” piped up the page. “but what’s he going to drink?”

“Didn’t you say he lives by the waterside?”

“Oh yes. Of course, sir. A peasant couldn’t drink wine like a king…or a duke…” Pavel looked very humble.

“I see,” said Vaclav, screwing up his eyes, “make me feel worse, why don’t you. Alright – go to the cellar, and roll out a cask of the finest port wine onto the sled.

Pavel raced to obey, and by the time he returned, the Duke of Bohemia was wearing his thickest, fur lined cloak, stoutly belted at the waist, and an enormous furry hat that covered his ears and strapped under his chin. The page gasped. “Are you…..”

“Going to deliver? Of course we are! I wouldn’t trust the guards not to scoff the lot the second they got out of the gate!”

“We, my lord?”

“Of course, “we”…. I couldn’t drag and carry all this lot by myself, could I? It’s your lucky day out!”

The story will be concluded on December 26th, Boxing Day, or, appropriately enough, the Feast of St. Stephen.