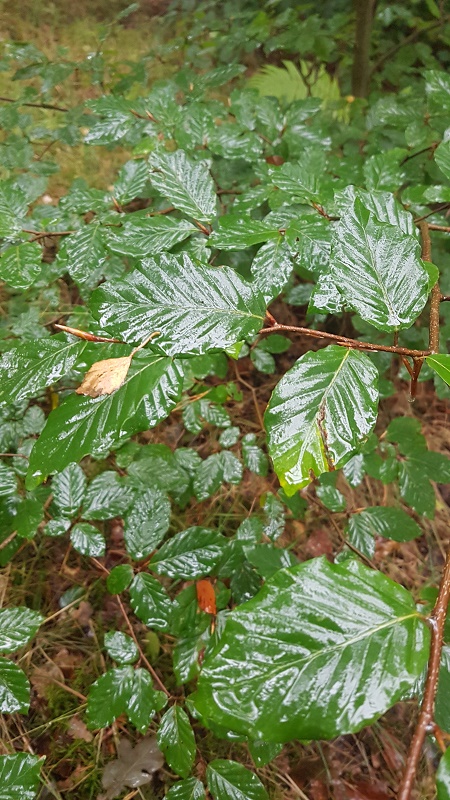

So today is Samhain. A Celtic festival to mark the end of summer, and the important transition between two parts of nature’s cycle. Because it is a cycle, it’s hard to know if its an ending or a beginning, both, or neither. But it’s a turning. mentally and physically, seen in the falling leaves and the settling of seed, heard in the song of the robin and the wild geese, smelt in the richness of fungal mould and felt in the night chilling of the air. We move with the season, from one place to another.

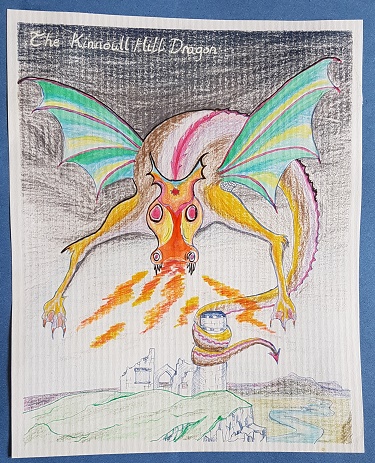

It’s also called Hallowe’en, or All Hallows Eve, and marks another transition, between the world of matter and the world of spirit. Some corners of the Earth are known as “thin” places. Some of the Hebridean islands are very thin. You go there, and time slows, the present meets past and future, you see things you’d never notice usually. You react in a different way. Hard to describe, but it’s like another world is almost tangible, separated from this by a filmy veil. Go there. You’ll get it. Well, at Samhain, that veil allegedly gets thinner everywhere, and people see things they didn’t know were there.

I’m not talking about plastic skeletons and vampire costumes and all that crap. The only vampires at Hallowe’en are the retail gluttons out to make a killing out of gullible, competitive parents intimidated by their offspring. Neither am I talking either about the demonisation and demeaning of innocent wise people (women mostly) into caricatures to hang in your window. Jamie Sixt of Scotland (James I of England) has a lot to answer for. And I’m certainly not interested in who has the biggest pumpkin! But yes, I am up for a good ghost story…..

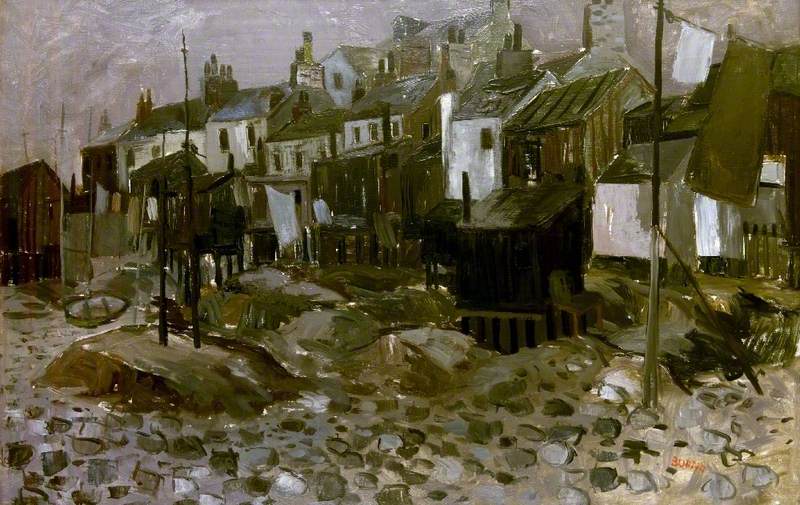

Not, thanks very much, those overblown, ludicrous, gory “horror” stories that just make me laugh or go back to a good book. I like the kind which are incomplete, lack a dénouement, are based on real experience, and for which it’s perfectly possible to find a rational explanation…. And yet…. There was the “haunted house” in Cornwall my family rented when I was 4 years old. All I truly remember was being terrified by strange noises coming from behind the wall, and not being able to sleep. A damp, underheated holiday home is highly likely to house rats, bats or other beasties in its cavities, who moved about at night. The tapping on the bedroom window my sister heard could be explained by an overactive teenaged imagination. The footsteps approaching the back door when no-one was there may have had something to do with my mother’s penchant for telling a good story. And we’ll never know now if, that morning when we came downstairs to find all the furniture moved about, my father had been up in the night playing a never-admitted scary joke on us. And yet….

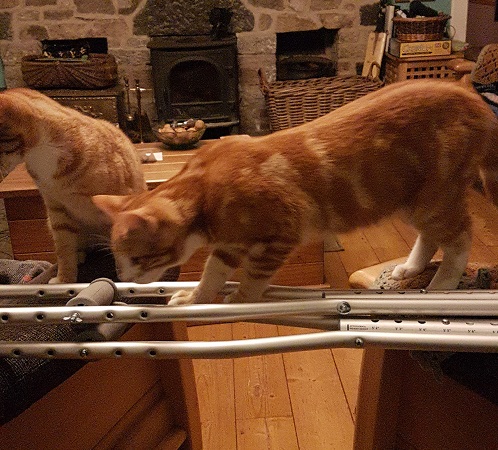

And there’s our “ghost” here at the cottage we’ve lived in for over 22 years. I used to see it a lot, but it’s been quiet the last couple of years. Avoiding Covid, no doubt. Just a figure, quickly scuttling along past the kitchen window, glimpsed out of the corner of your eye. Never does anything else, never knocks or makes any sound and never inside the house. It isn’t remotely scary. I never mentioned it to anyone for years, and then one day I started as usual as it went by and Andrew, sat in the kitchen with me, said, “Oh, was that her again?” Andrew is the most resistant and sceptical person I know who scoffs at anything remotely “supernatural” (while being secretly scared!), but he “sees” the figure as distinctly female, head covered in a shawl. “Like the Scottish Widows advert”, he says.

Easily explained! any one of a number of “tricks of the light”. I tried to pin it to our reflection in the glass when the kitchen light is on, and yet it appears in broad daylight when there’s no reflection as well. Anyway, we have missed it/her in this period of absence, though we both saw her one afternoon last week. Maybe tonight, when the veil thins, and the world turns……?