If you take the road from Perth to Dundee, you skirt the edges of an explosion of geological delight known as Kinnoull Hill. Sheer cliffs soar up from sea level on your left. In autumn they are swaddled in the glorious golds and browns of beech woodland at the base; in spring and summer studded with the gold of gorse and broom. Dilapidated towers seem to teeter on the edge of the cliffs looking like something Germanic from a Grimm fairy tale (they were put there fore that very purpose).

These dramatic cliffs are the result of volcanic activity some 400 million years ago when a monstrous intrusion of magma elbowed its way through the older rocks in an enormous seam and solidified. Much later, the Kinnoull Hill geological intrusion was part of other monster-scale earth movements – the folding which left us with the Sidlaws on the north side of the Tay and the Ochil hills on the other (it’s called an anticline; think of a rainbow….). Subsequent faultlines and erosion removed the top of a rainbow and created the deep valley through which the Tay now marches triumphantly to the sea.

If, however, you approach these cliffs from the other side, the ascent is appreciable, but mild and steady, the slow, back-door rise of the escarpment. I went that way in April, and parked in the Corsie quarry, where volcanic dolerite and basalt is exposed, and from which it was taken for building for centuries. Up a steep bank, and a variety of paths are on offer, taking me first to the trig. point on Corsie Hill and fine views north over the small city of Perth and the vast breadbasket of Strathmore, to the mountains of the Angus glens to the east and the Obneys, marker-hills of the Highland Boundary Fault, slightly west. Up through roads and sheltered by woodland I went on winding tracks. Oak and birch dominate in places, in others, beech and non-native conifers stake a much-contested claim. Areas of heath and rough grassland house woodland sculpture in this popular spot.

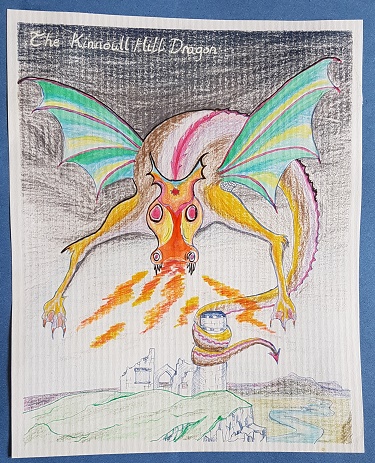

Sometime between all that geology and now, we are told, a dragon arrived on Kinnoull Hill. It glided along the unassailable cliff edges until it found a crevice, leading into a large enough cave for a small dragon to set up shop. This cave, called the Dragon Hole, is high on the cliff and allegedly could hold a dozen adult persons, so it wasn’t luxury accommodation for a dragon. What the dragon got up to, to upset the people of St. Johnstoun (as Perth was then known), I have no idea, but as is the way with relationships between human animals and animals either good to eat or a tad scary, someone was said to have “slain” it. It could have been St. Serf (what IS it with saints and dragons??), commemorated as a dragon slayer in the old church at nearby Dunning.

But my bet is Serf made it up, and the dragon’s still about, somewhere. There is a record that in the late 13th century (first) wars of independence, none other than William Wallace “pressed by the foe, occasionally betook himself to the retreat of the Dragon’s Hole.” In the 16th century, it was the local custom for a procession of youngsters from the town to clamber up to the Dragon Hole on May 1st (the pagan feast-day of Beltane), with garlands of flowers, musical instruments, and what may have been a Green Man. Or was it a dragon, representing the sun god, Bel? Whichever, it certainly cheesed off the local minister. In 1580, the congregation of the Kirk were forbidden to “resort or repair” to the Dragon Hole, on pain of a £20 fine (quite a fortune in those days) and repentance in the presence of the people.

You might think that was the end of it, and the Dragon Hole, together with its occupant, faded and disappeared from local knowledge. I used to teach about landscape character and interpretation, among other things, to Countryside Management students at the local college, and used Kinnoull Hill as a case study. One year, a couple of the lads got quite excited about dragons (can’t think where they got that from), and vowed to find the Dragon Hole. But here’s the thing: their colleague Arlene, a local girl, told us she used to go there as a child and had been let into the secret of its location by an older relative. She also had the good advice that they should not attempt to climb up to it, but abseil down. They went off in cahoots. Term ended before I ever heard if Ryan and Hamish were successful. Knowing them, I wouldn’t be surprised.

Back to my walk. I came out to the viewpoint on the edge of Kinnoull Hill cliffs, where the ground suddenly ends, and bunches of flowers tell sad stories and remind us of human misery. The views downriver, with Dundee sparkling in the distance, and across to the greens and golds of Fife, with it’s own matching quarries and volcanoes, were more than worth the uphill slog. Everything, especially life, seemed precious to me then. I remembered the tales of the dragon’s hoard of treasure, the enchanted “dragon-stone” which James Keddie found in the Dragon Hole in 1600, the “Kinnoull Diamonds” that are said to sparkle by night. And I came right back to geology. Around volcanic intrusions, mineral-rich deposits hold many semi-precious and maybe precious stones – on Kinnoull Hill, it’s garnets and agates that are best known.

Back down to Earth, in every sense!