The little wood that lies an easy walking distance from my house is juvenile. It was planted maybe twenty-five years ago, mostly with hazel trees that have grown with multi-stemmed enthusiasm, peppered with birch and rowan, interspersed with tall sycamores and oak trees, now starting to muscle their way above the copse. Blown-in elder, and suckering blackthorn garland the woodland fringes. There are literally thousands of small ash seedlings covering much of the woodland floor; few-to-no surviving older ash trees. I wonder how these babies will fare in the aftermath of ash die-back disease. A large proportion are annually grazed out by deer; there are hares and hedgehogs hanging out in the top part of the wood, and I’ve seen red squirrels using the wood as an aerial highway. They, and other small mammals, feast on the hazelnuts in winter. This year, I heard and saw flashy jays on the rampage, and I’m seeing hazelnut stashes which may be their doing.

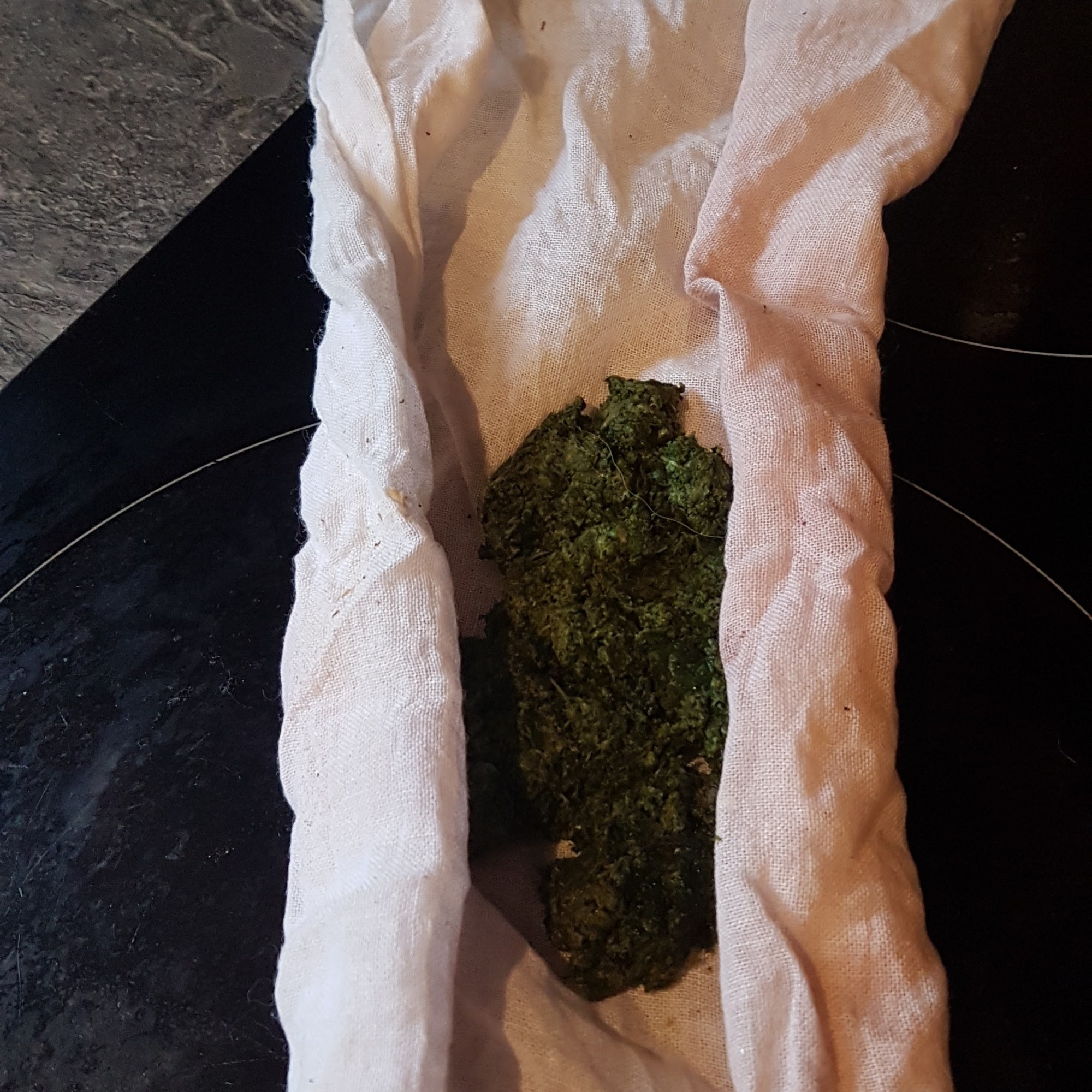

I’ve always referred to the wood, with unintentional and misplaced territorialism, as my larder. It contained the best patch of nettle shoots for soups, teas and pesto for miles, though these have now shifted as the shade has increased. In early summer, an army of Common Hogweed supplies me with chunky flower-buds to make my favorite pakoras or to braise as a vegetable. One day, I may be obliged to harvest the seeds to make flour; it’s as well the species is expanding its range. About the same time, elderflowers are picked for cordial or champagne, or just to eat. As summer winds on, the patch of feral raspberries in the clearing start to ripen. This year, they were pretty poor though, as are the ones in the garden. I’m not sure why. Competition from the broom, perhaps, whose yellow flower buds go into my May salad bowl.

I harvest the hazelnuts haphazardly; the trees I used to pick from now bear their nuts too high for me to reach – I either wait for the profligate mammalian and avian foragers to knock them to the ground or I gather from smaller trees, self-seeded from nuts none of us ate, or from trees on the edge. When I have enough and they are shedding their frilly petticoats, I shell and roast them to get the lovely chocolatey smell. Usually, about half the shells are empty.

The hazel wood is also the store I visit for the likes of washing-line props, bean-poles, and pea-sticks. No need to cut these poles, as regular storms bring more down; the forest floor is littered with useful sticks for every purpose, not least, lighting the stove. Children collect the long ones and build them into dens.

Today, I’m collecting rowan berries for the sharp, rich red jelly we’ve always had as a family to accompany Christmas dinner, and thereafter, everything else. The young rowan trees bear copious fruit, but I have my personal favorite trees, where the berries are larger, a feistier red or more juicy. I note the elderberries are nearly at picking stage, too – a winter essential for medicinal elderberry vinegar, or, mixed with hips from the wild roses along the field edge, a soothing syrup. Likewise, there is a particular hawthorn bush that has fruits large and sweet enough to stop and nibble at while contemplating the sunset or sheltering from a cloudburst. They make good liqueurs.

I gather a couple of Brown Birch Bolete mushrooms as well. It was a fair few years ago now that these edible fungi began to appear around one of the multi-stemmed birch trees. I don’t pick many, and am always watching for new patches of fruiting bodies as the mycelium spreads to other birches. It’s been fascinating watching how the fungal flora in the little wood has gradually established itself as the trees grew, and fungal threads found their roots, to embark on that precious, beneficial relationship that entangles both and is called the mycorrhizae (“fungus-roots”). The species I find have changed over the years, and will continue to do so. I hope more edible species will arrive soon. The Birch Boletes I don’t have for breakfast will be dried for the winter.

Will it be a good year for sloes? There have been crops from the blackthorns on the field edge so fantastic I’ve stopped making sloe gin for a while. Maybe time for another batch. The blossom was there in March, so I’ll check it out. If there are sloes, I’ll wait for the first frosts to make them tingle, and see if the birds have spared me any.

Later, when the leaves fall in tawny profusion, and the rose-bay willow herb from which I selected early shoots in spring for fake asparagus has shed its seeds, when the air starts to nip and my breath makes clouds, I’ll harvest the peace of the woods, the melancholy inertia, the stand-and-stare compulsion of fractal twigs and branches and the patterns on bark.

And perhaps pick curly, frosty old flower-stems of the willow herb to decorate the house for Christmas.