There are different kinds of walks-with-mushrooms. My first, fifty years ago, were cataloguing walks, an academic exercise that became an obsession. A specimen of each would be removed and bagged (no smartphones then, and my Kodak Instamatic didn’t really cut the mustard, though I did try), taken home, pored over for hours to try to identify it, and then a spore print taken. This was all in the cause of a college Rural Studies project that I somehow never grew out of.

When I began to differentiate the ones I could eat from the poisonous ones, foraging AND cataloguing walks happened – a basket for the ones I knew I could eat, and another for the unknowns. Many remained – and remain – unknown, something which used to really bother me. However much later when I was regularly leading foraging walks, I realised that so long as I could recognise the “edible and good” fungi and the poisonous and dodgy ones, most people were happy if we could pin the “small brown jobs” down as far as a genus.

I still take huge interest in identifying weird or remarkable specimens that I’ve never seen before, but these days I’ve discovered the pleasure of walks-with-no-purpose-with mushrooms. This walk, meandering along the River Tay from Dunkeld, had no particular object but to be captivated by the surprise and beauty of the fungal kingdom – so often misrepresented, under-valued, the importance of which is not understood by the majority of humans.

First came a phenomenal display of Fly Agarics, the mushroom of the shamans, too exquisite to pass by, shouting their wares, nestling in ground which was once birchwood. Their mycelium is always entangled with the roots of birch; from the beginnings of plants on dry land they have needed each other. They start as big white crusty buttons, the red skin of the cap breaking through the veil to leave those fairly-tale white “spots”. The cap expands, the spores fall. One was nearly as big as my head.

Troops of Bonnet mushrooms, various types, marched over fallen trees and gossiped in crevices of stumps, glistening in the sunlight. Shiny black excrescences of Witch’s Butter erupted from dead wood. Amethyst Deceivers – which I could have picked for eating but didn’t – showed all their colour range from vivid purple to washed-out grey. In the leaf-litter, the Destroying Angel, related to the Fly Agaric but far more deadly, glowed purest white. Such a potent name for a poisonous mushroom!

Across the track lay a small segment of a huge fairy ring of an enormous mushroom commonly called the Giant Funnel Cap (check the size 8 boot in the photo for scale). This took me immediately back to those student Rural Studies Days, when I first saw this mushroom in local woods, in a ring that was actually measurable. From the fresh fruiting bodies came a strange, un-mushroomy smell. I took one home, identified it easily and, as the book said edible, fried it in slices. It tasted like its smell – like nothing I’d ever encountered. To this day, I’m still trying to work out if I actually like it! But size-wise, they are easy pickings, and it’s fun to estimate the equally astounding diameter of their fairy-rings and plough through the woods to try to find the mushrooms on the other side of it.

This walk wasn’t for foraging, for worrying about what I was looking at, and I haven’t bothered to tease apart the various fairy bonnets. Old habits die hard, but really, I don’t need to know!

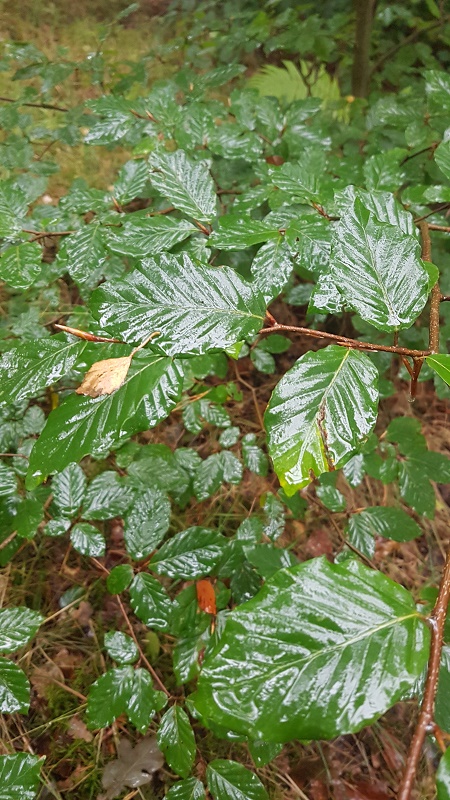

A full evening, two nights and two days of rain. Humidity hangs in the air, the soil beneath my feet pulses damply, the mosses are full and green. Raindrops still coat every flower of grass and frond of bracken, but the sun is shining. The timing is right.

A full evening, two nights and two days of rain. Humidity hangs in the air, the soil beneath my feet pulses damply, the mosses are full and green. Raindrops still coat every flower of grass and frond of bracken, but the sun is shining. The timing is right. surviving the metallic blundering of the foresters’ vehicles, harvesters and forwarders, along the track. How did it get here? Not a native tree, so planted a long time ago, when this haphazard forest was occupied in a different way. Who planted it? Did they hope for chestnuts to roast on autumn fires?

surviving the metallic blundering of the foresters’ vehicles, harvesters and forwarders, along the track. How did it get here? Not a native tree, so planted a long time ago, when this haphazard forest was occupied in a different way. Who planted it? Did they hope for chestnuts to roast on autumn fires?