On a quiet day of winter sun and muted activity from woodland birds, I arrive at King’s Myre again. Reed Mace flowerheads from last year cluster around the watery margin, clogging the channel by the little jetty where the boats wait and fill with rain. We used to call them “bulrushes” where I grew up, and it wasn’t till Mr. Illesley, in Rural Studies, enlightened us all about the differences between reeds, rushes, sedges and grasses that I ever learned their proper name– or that Reed Mace is related, but none of these anyway!

It is the same plant known as cattails in America, and valued throughout its distribution for its edibility. The rhizomes – root like underground stems, or underwater ones in the case of this plant – are starchy and filling when baked. They can also be dried and ground into flour, though I never have. The pollen from the male flowers can be used as flour too, or to thicken sauces and soups. It has many medicinal uses. But the best part is the emerging shoot – which will be appearing above water level any time now. Cut, cleaned, steamed, baked, sauteed – it is a lovely spring vegetable to rivals asparagus or bamboo shoots for flavour and versatility. You can keep eating the shoots until the flower spikes start to emerge, you don’t need waders to forage it, and, as Reed Mace is actually quite an invasive plant, it’s pretty sustainable to nibble bits off the clump! Last year’s flowers are starting to burst apart now, revealing the dense, cottony-fluffy seedheads inside.

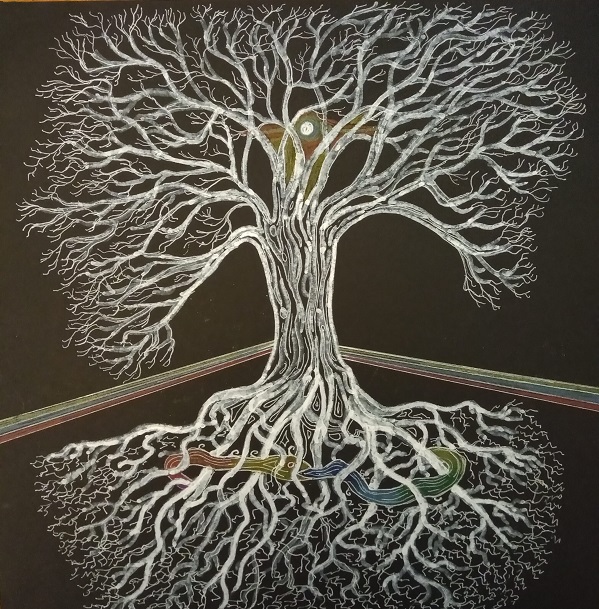

I creep through the spongy, saturated margins of the little loch at the heart of the King’s Myre, to peer through the cattails to see what wintering birds are on it today. Goldeneye, a few gadwall, mallards, a coot, typically swimming against the tide of the rest, intent on his own adventure. No sign of the swans, too early for the osprey to be home yet. In the damp woodland, waterlogged alcoves and scrapes, from which spiky, angular trees grow erratically, wait for frogs and toads to arrive for spawning. Between bare branches, multiple trunks and stems and a storm of tiny twigs, the blue sky seeps as if caught in a vast, arboreal net, reflected in patches of water.

Bracket fungi show off their smug Cornish-pasty smiles of concentric bands, on wood they share with moss and lichen, and a thousand invertebrates. Spread across the leaf-carpeted floor, long-dead logs, un-barked, silvery, yielding, are home to thousands and thousands more, riddled with holes and channels and hidden tunnels in the fungus-softened wood. On cue, somewhere in a dead tree, a woodpecker begins his first tentative drumming and drilling.

I look up into the Scots Pines, their narrow crowns dancing around each other like polite or nervous teenagers, and see the shapes of jagged sashes of sky, so clear, so blue….

Look up, look through, look between – there is much to see. Or is there only sky?